Undoubtedly, one of the greatest scientific advancements in our lifetime, along with the sequencing of the human genome, is the profiling of the microbiome. Most people have heard the estimate that we are only “10% human” or that foreign bacterial cells outnumber human cells 10 to 1. New data shows that number is closer to a 50:50 ratio. More accurately, we are 50% human.1 The microbiota exhibits all the characteristics and metabolic activity to be officially categorized as its own “organ.”2

However, our foreign bacteria have 100 times the genetic diversity and potential of our own DNA. This means they have 100 times the genes that can be flipped on and off through various stimuli, like interaction with each other, metabolites, toxins, exercise and diet.3 The genetic output of our microbial population includes the production of proteins that may signal our own genes to act, either turning them on or off.4,5

In fact, our microbiota produce nearly 30 different kinds of neurotransmitters, identical to the ones we make in our brain; plus, they manufacture and mediate thousands of immune- or inflammation-modulating molecules.6,7,8,9 The far-reaching impact of our symbiotic relationship with our microbiota influences brain, heart and liver health; the development and etiology of allergic and skin diseases; metabolic efficiency; drug pharmacokinetics; and immune and digestive function.10,11 The ability to manipulate this population for our good is a major constituent of epigenetics and personized nutrition.12,13

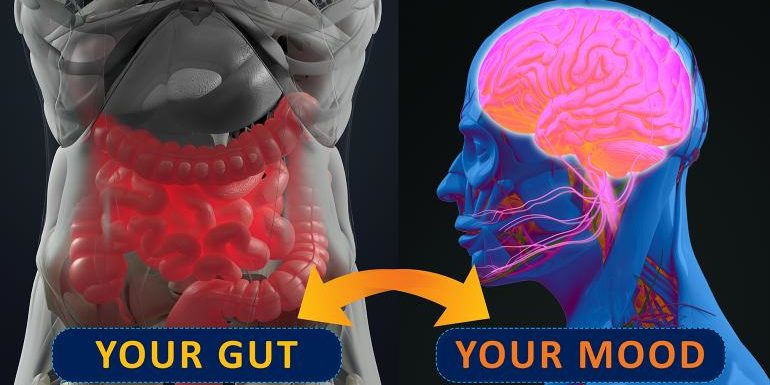

The gut is increasingly referred to as the “second brain.” The gut contains more than 100 to 500 million neurons, exceeding the number of neurons found in the spine.8,14,15

The brain is the manager and sorter of all the stimuli we receive from the outside world. We mainly think of this as what we hear, see and touch, but we forget about the vast amount of data processed via the gut.16 It is no wonder that we have long noticed gastrointestinal (GI) complaints associated with depression, anxiety, insomnia and many other diseases we previously thought of as solely “mental” illnesses.17,18,19 Conversely, for nearly a century, many gut diseases, like irritable bowel disease, were described as “nervous disorders.”

The two-way communication between the gut and the brain via the enteral nervous system (ENS) and the vagal nerve is called the “gut-brain” axis.20,21 Science is still elucidating the complex pathways of communication between the brain and the gut that include hormone signaling, microbial metabolite production and immune system activation.22,23 We already know that enteric nervous system hormones and peptides can make their way into circulation, and more importantly, cross the blood–brain barrier acting synergistically to regulate mood, cognitive function, stress, appetite and sleep.24,25

The communication via the gut-brain axis goes both ways. This is especially evident when stress is introduced. Even short-term exposure to stress can impact the microbiota community profile and lead to dysbiosis by altering the relative proportions of the main microbiota families. This dysbiosis in turn influences stress responsiveness, anxiety-like behavior and the set point for activation of the HPA stress axis.

Read The Full Article HERE